Climate change was considered the defining issue in the recent Australian federal election when the conservative coalition government was voted out of office. Next, the new Australian parliament must deliver on a mandate for “game-changing climate action” (Climate Council 2022). All sectors, including the performing arts, will need to keep up the pressure on government and industry to make up for over a decade of belligerent denialism and inaction. The outgoing regime had waged “climate wars” against any reduction of carbon emissions, extending the country’s dependence on an extractivist coal-rich economy and, in the process, becoming an outlier at global forums, especially COPs 25 and 26 in Madrid and Glasgow. The background to this position is that Australia is one of the world’s biggest carbon emitters on a per capita basis. It has the third-highest reserves of coal after the USA and Russia and is a major coal exporter to Japanese, Chinese, and Indian markets, feeding a demand that will decline as net-zero targets come into play (Geoscience Australia 2021; Giggacher Reference Giggacher2022).

A key problem impeding the necessary shift to renewable energy is the “settler-colonialism” mindset (Wolfe Reference Wolfe1999:2), dating back to the late 18th century when the primary drive was to eliminate native societies and use traditional lands for “capitalist accumulation” including resource extraction (Howlett and Lawrence Reference Howlett and Lawrence2019:883). Also known as “quarry vision,” there is an abiding belief that Australia’s greatest asset is its “mineral and energy resources—coal above all” (Pearce Reference Pearce2009:1). Until recently, the idea of leaving reserves in the ground has been inconceivable, portrayed as a conspiracy by doom-mongers, and an existential threat to the Australian way of life. An iconic performative moment of reactivism and denialism in the recent climate wars and other performances help us identify how pressure can continue to be brought to bear on the framers of political and cultural policy.

Among the many forms of reactivism, one of the most defiantly theatrical was a performance in the Australian Parliament in 2017 that became known as “coal theatrics” (Hunt Reference Hunt2017; see also Varney Reference Varney2022). This occurred when the former treasurer, later prime minister, Scott Morrison, held up a lump of Australian black coal during a Parliamentary sitting. Mocking the demonization of coal, he delivered the punchline: “This is coal… Don’t be afraid, don’t be scared, it won’t hurt you. It’s coal” (in Hamilton Reference Hamilton2017). His colleagues sniggered and passed it around, enjoying the stunt (fig. 1). As Katharine Murphy described it in The Guardian: “What a bunch of clowns, hamming it up” (2017). Meanwhile, outside, another record-breaking heatwave was under way. Footnote 1 The performance sought to naturalize coal as harmless, inert matter, cleaned, polished, and lacquered for the occasion and not responsible for anything as grand as global warming.

Figure 1. Treasurer Scott Morrison hands Deputy Prime Minister Barnaby Joyce a lump of coal in the House of Representatives at Parliament House in Canberra, Australia, 9 February 2017. (Photo by AAP/Mick Tsikas)

Ethicist Clive Hamilton described Morrison’s performance as akin to King Lear raging in the storm “defying nature to do its worst, almost willing it to happen because mankind will prevail” (2017). Framing Morrison as Lear evokes the fatal combination of foolishness, egotism, and denial. Implicit within the theatrical reference is the ruler-king holding forth while in the thrall of mining lobbyists who whisper in his ear like Regan and Goneril, luring the patriarch with flattery. But the conservative party’s “coal theatrics” had none of the gravitas of tragedy. It was a melodramatic or even hysterical response to global pressure to phase out fossil-fuel energy production and its related exports. Today Lear has been forced to acknowledge that he chose the wrong daughter as Australia makes the transition to an economy based in renewable energy.

The tendency of the previous government to theatricalize the climate wars was intended as a distraction from the seriousness of the problem. Certain performance artists are responding in more clear-headed and constructive ways to the complex embeddedness of coal in Australian culture. In 2013, for example, coinciding with the beginnings of the climate wars, artists Norie Neumark and Maria Miranda, as the collaborative creative team Out-of-Sync, presented CoalFace in a Melbourne gallery (Neumark and Miranda Reference Neumark and Miranda2013). This was a performance installation in which the artists interacted with mounds of brown coal placed on the gallery floor and played with a toy pick-up truck loaded with coal and branded with the logo “FASTLANE CONSTRUCTION CO” (fig. 2). The public was invited to enter into a tactile relationship with coal dust by smearing it on the white walls of the gallery, an experience that for many was a first encounter with the material that powers our lives.

Figure 2. Norie Neumark in CoalFace, The Library Artspace, Melbourne, 28–30 November, 2013. (Photo courtesy of Norie Neumark and Maria Miranda)

In a more symbolic mode, a lump of coal was displayed on a clean, white plinth next to a small green plant in a glass vase. The co-presence of the coal and the living plant on the plinth seemed to propose a relationship between the two disparate objects, the one seemingly “dirty” and dead, the other “clean,” signifying new life. This staging is quietly suggestive of the prehistoric roots of fossilization whereby the young plant begins the long geological process of coal-becoming. By these means, the installation aestheticized coal as an object of contemplation, a tangible presence, and simultaneously, the product of deep evolutionary processes. In doing so, it mapped coal’s post-utilitarian future as a museum object while its carbon traces continue to circulate in the earth’s atmosphere.

The interactive nature of CoalFace provided opportunity for spectators’ sensorial experimentation and imaginative wonderings on the themes of scale and deep time. Reviewer Meredith Rogers described its profound impact on her perspective of the human in nature:

I came away thinking, almost dreaming, of the dense, dripping temperate rainforests of Gippsland; their slow processes of laying down change; their lush indifference to small-scale, individual humans. Perhaps it is in re-igniting this love (I can’t think of a better word) that CoalFace makes its strongest appeal against the depredations we collective humans are wreaking on our only home/our own/only body. (2014:20)

The return of emotion to critical discourse is not sentimental; rather, it recognizes the pain of self-harm that accompanies an extractivist mode of living.

CoalFace developed out of a month-long residency in Beijing where the artists used a phone app to measure the daily AQI (Air Quality Index), revealing dangerously high levels of particulate matter (PM2.5), and more than likely the product of Australian coal exports (Neumark in Neumark and Miranda Reference Neumark and Miranda2014). Footnote 2 The artists’ visceral experience of the globally networked nature of the fossil fuel industry translated into a performance that altered spectators’ perception (even for a few moments) of an object that is ubiquitous in our lives but from which we are ordinarily estranged. Neither activism nor reactivism, the installation represents a gentle, meditative approach evoking a theatricality that highlights the materiality of coal in stark contrast to its carbon releasing combustible properties. In doing so, performance finds ways to offer an alternative mode of engaging with the multifaceted problem of coal and its deep entanglement in the Australian economy and way of life.

Neumark and Miranda sourced the coal for CoalFace from the Latrobe Valley in Victoria, which contains 65 billion tons of brown coal, estimated to be equivalent to 25% of the world reserves. This region is home to Hazelwood Power Station, Australia’s most polluting coal-fired facility. In February 2014, the open-cut coal mine that serviced the power station caught fire. Artist Hartmut Veit was living and making artworks in the region when the crisis erupted. As the fire burned for over 45 days, causing the worst air pollution event to date in the nation, the community of the regional township of Morwell grappled with a severe health crisis, enforced relocation, and the prospect of lost livelihoods (Hopkin Reference Hopkin2014).

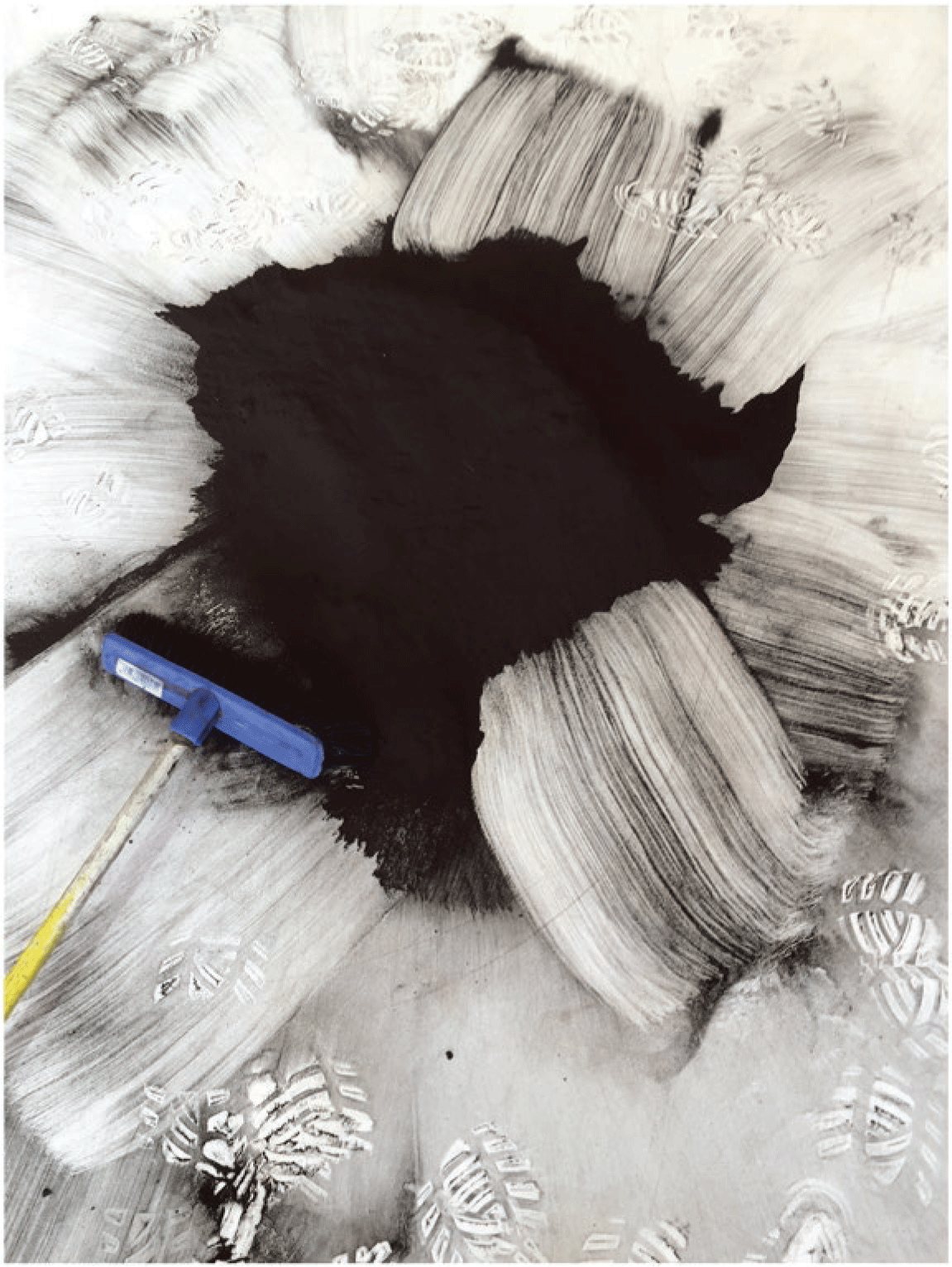

Taking up residence in an abandoned shop he turned into a gallery space, or a white box theatre, Veit devised a series of works entitled COAL (2014–2017) (fig. 3). Reminiscent of Neumark and Miranda’s CoalFace, Veit invited the local community into the gallery to experiment with black coal dust on the floor and on white paper. Key to the project is what happens artistically and emotionally for the community when engaging with the materiality of coal-as-object. Working with a professional trauma psychologist, Veit provided the local people with opportunities to speak about complex emotional relationships with coal and its effect on health and livelihood, as well as concerns about a just transition for workers in the move to renewable power generation. When Veit turned a shop into a gallery, he demonstrated what can happen when capitalism is replaced by not-for-profit community building and creativity. His compassionate and empathetic performances offered the space of recognition for imminent loss—of employment, the continuity of family narratives about generations of coalminers, and a once secure future.

Figure 3. Coal Painting, Morwell, Australia, 2016. (Photo by Hartmut Veit)

The coal-driven Australian economy is today entering a period of transition that will be complicated and difficult. Artists and others need to keep up the pressure on leadership in the shift from denialism and reactivism to action. If it is going to play its part, performance must be able to drill down to the conflicting realities and emotions at the heart of the transition to renewable energy. Australian artists like Neumark, Miranda, and Veit, who continue to make new work, Footnote 3 offer a less hysterical and slower, more contemplative approach than “coal theatrics.” By turning galleries or performance spaces into places of reckoning with the future of coal, artists can make room for mature and difficult conversations. They can rehearse nonextractivist ways of engaging with humans and nonhumans that align with and draw from Indigenous knowledge around kin and care, a philosophy of living with and not on the land (see for example Wright Reference Wright2019; Climarte 2022).

Just as the new parliament needs to enact legislation and policy on environmental action, artists need to continue to find innovative and creative ways to unsettle ossified and outmoded “wisdoms” such as the superiority of humans over nature, quarry vision, and the relentless drive for capitalist accumulation (including within the renewable sector). In this moment of national change, Australia is seeking to understand its new role in the global order of climate action. To frame the question as Lear does: “Who is it that can tell me who I am?” (1.4.212), the answer must lie in our connectedness with the environment. By working in the registers of the emotional, the embodied, and the perceptual, artists can take a lead in offering spaces for imagining postcoal future scenarios while acknowledging the unmitigated damage in the present.