Invisible to the legal system: The policies adopted in Italy concerning citizenship for children of immigrants

“We are defined as second generation immigrants. Lately, I see it everywhere. Immigrants from where? From our mothers’ womb? […] It seems like immigration is a genetic defect, something that is passed on generation to generation, like a life long sentence that you pay for your whole life.” (Translated into English by the author)

This is how Igiaba Scego, daughter of two Turkish immigrants, describes the situation of children of immigrants who are born in Italy or are brought to Italy at a young age in an article for Internazionale. According to the report (1.8Mb pdf) of the Italian national statistical institute (ISTAT), on January 2018 the number of minors falling within these categories was one million 316. 75 per cent of this figure were children belonging to the so-called “second generation”, while the 25 per cent were children who came to Italy at a young age and are defined in academia as “1.5 generation” immigrants. These children are still labeled as immigrants and are not considered Italian citizens by the State, even if they live their life as their Italian born peers and they speak the same language.

Italian citizenship is currently regulated by Law No. 91/1992, which foresees two main different ways for children of immigrants to acquire citizenship:

- Ius soli – children born in Italy to foreign parents acquire the citizenship through application within one year after coming of age 18 and providing uninterrupted and legal residence in Italy since birth

- Ordinary naturalization – children not born in the country become citizens after 10 years of residency for non-EU immigrants; 5 for refugees and stateless persons; 4 for EU immigrants; 3 (2 if minor) for immigrants of Italian origin. In these cases the State requires a minimum income limit

Both procedures require an application that can be rejected and can cost between 300 and 400 euros. The whole process can last up to six years. This means that children born in Italy to foreign parents are not considered Italians in their own country. Furthermore, until the age of 18 they will have to renew the visa to stay in Italy.

A law reform was discussed several times during the past 10 years, but no major amendments to the above-mentioned legal framework have been made so far. In 2012 the topic arose to the public eye with the campaign “L’Italia sono anch’io” (I’m Italy too). It consisted of several public events aimed to collect the over 200-thousand signatures required to present a citizens’ initiative bill (125Kb pdf) to the Italian Parliament. Three years later, the bill was approved by one of the two Chambers of the Italian Parliament, “Camera dei Deputati”, even if with a modified text. Unfortunately, it was ultimately delayed on the Senate floor, the other House of the Parliament. The two main points foreseen by the proposal were: the extension of ius soli to children born to immigrants parents that would acquire the citizenship at birth if one of the parents has permanent European visa; and the introduction of a new category ius culturae: minors born in Italy of parents without a permanent visa or arrived in Italy before the age of 12 could acquire the citizenship after attending for at least 5 years a school cycle.

Year after year the political sphere overlooked the topic, while associations as “G2” and “Italiani senza cittadianza” (Italians without citizenship) have been raising their voice for this considerably big part of the population that seem to be treated like ghosts. Ghosts, that is how this group feels like and how it has been described several times by major Italian newspapers.

Having the right to vote when at age, being free to go on a school trips without having to go back and forth to get all the visas and documents, being able to participate to public tenders, not living with the terror to be deported to a country they barely know, not having a passport in a language that in many cases they don’t understand, not feeling excluded and forgotten. These are some of the things that children of immigrants cannot do.

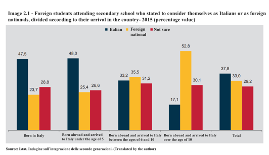

As shown by the statistics provided by ISTAT, most of these individuals already feel Italian and a part of the society. Furthermore, migration is questionably a choice for adults, but is for sure not a choice for children. It is rather something they passively experience. Consequently one may wonder: why should that penalise their life? It seems only fair for Italian policies to become more inclusive.

As shown by the statistics provided by ISTAT, most of these individuals already feel Italian and a part of the society. Furthermore, migration is questionably a choice for adults, but is for sure not a choice for children. It is rather something they passively experience. Consequently one may wonder: why should that penalise their life? It seems only fair for Italian policies to become more inclusive.

Short biography

Anna Siniscalchi is a student at University of Bologna where she attends the International Master Degree Program in Language, Society and Communication. She holds a Bachelor Degree in Mediation and Translation Science from University of Salento. During her academic path she did many experiences in international environments both for work and study reasons, she lived several months in Lisbon, Berlin and Paris. The main focuses of her studies are cultures and languages. Her interests include minorities’ rights, humanitarian communication and the role of language on in crisis situations