Aboriginal Child Language Acquisition Project (ACLA1)

ACLA1

Overview

Chief investigators

Professor Gillian Wigglesworth, Dr Patrick McConvell (AIATSIS), Dr Jane Simpson (University of Sydney)

Type

ARC Discovery Grant (2004-2007)

ACLA2

Visit the ACLA2 research project website

The Aboriginal Child Language Project was funded by an Australian Research Council Discovery Grant. The project investigated the type of input children receive in multilingual environments that include a traditional language, a contact variety of English and code-mixing between languages and speech styles. It involved case studies of three Aboriginal communities and was designed to address the following questions:

- RQ1: what kind of language input do indigenous Australian Aboriginal children receive from traditional indigenous languages, Kriol and varieties of English, and from code-switching involving these languages as used by adults and older children?

- RQ2: what effect does this have on the children's language acquisition and how the input is reflected in their productive output?

- RQ3: what are the processes of language shift, maintenance and change which may be hypothesised to result from this multilingual environment, as evidenced by the children's input and output and the degree to which this reflects transmission of the target languages, the loss of traditional languages, or the emergence of new mixed languages?

To address the complexity of these questions, this project brought together people with expertise in three different, but related, fields: Central Australian languages (Disbray, McConvell, Meakins, Moses, O'Shannessy and Simpson), first language acquisition (Wigglesworth), and historical change and language maintenance (McConvell and Simpson).

The research team collected the data for the study in four main locations: Kalkaringi, Lajamanu, Tennant Creek, and Yakanarra. We identified the kinds of interactions young children are involved in, the language they use at different ages, and the breadth and variety of language the children are hearing. Additionally Carmel O'Shannessy (then PhD candidate at MPI, Nijmegen and University of Sydney) studied children's acquisition of Light Warlpiri and Warlpiri at Lajamanu.

Samantha Smiler Nangala-Nanaku telling a story to her son based on a picture-prompt book

Contact acquisition

Many children in many communities in the world grow up in communities in which the language situation is increasingly fluid, and where the acquisition of more than one language is the norm.

People move between languages, depending on who they are talking to, and what they are talking about.

In language contact situations, new languages may emerge, sometimes categorisable as creoles, sometimes as mixed languages. These languages enter the repertoire of languages that speakers move between.

Children growing up in such communities hear their sisters, brothers, parents and friends and relatives speak traditional languages as well as the emerging languages, and they hear people switch readily between these languages.

How children in these multilingual environments learn to talk, what languages they use, what languages they hear, and how they interact with people in such communities are what we are calling "contact acquisition".

Languages

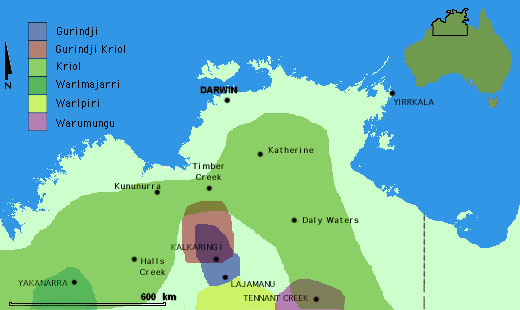

Please note: this map is a combination of areas where languages were traditionally spoken and areas of current speaker distribution, especially in relation to new languages such as Kriol.

-

Gurindji

Typology

Gurindji is a suffixing Pama-Nyungan language spoken in the north-west of Australia, particularly in Kalkaringi and Dagaragu. It is a member of the Ngumbin subgroup of languages which includes Ngarinyman, Bilinara, Malngin, Nyininy, Mudburra, Jaru and Warlmatjarri. Gurindji is an endangered language, with only 60 speakers remaining in 2003. Gurindji Kriol is the language transmitted to the new generation at present.

Phonologically, Gurindji is a fairly typical Pama-Nyungan language. It contains stops and nasals which have five corresponding places of articulation (bilabial, apico-alveolar, retroflex, palatal and velar), three laterals (apico-alveolar, retroflex, palatal), two rhotics (trill/flap and retroflex continuant), two semivowels (bilabial and palatal) and three vowels (a, i, u). Combinations of semivowels and vowels produce diphthong-like sounds. Like most Pama-Nyungan languages, Gurindji is notable because it contains no fricatives or a voicing contrast between stops. Stress is word initial, and syllables pattern CV, CVC or CVCC.

Gurindji is a dependent marking language. Word order is relatively free, though constrained by discourse functions. The verb phrase is made up of a free coverb and an inflecting verb which contains information about tense, mood, modality. Bound pronouns also attach to the inflecting verb to cross reference subjects and objects for person and number. These pronouns inflect for nominative and accusative case, unlike free pronouns whose form only changes for dative case.

The noun phrase may contain nouns, adjectives, demonstratives and free pronouns. Case marking for nouns is ergatively patterned, and generally other elements in the noun phrase must agree with noun's case.

References

- Lee, Jason and Dickson, Greg. State of indigenous languages of the Katherine region. Katherine: Diwurruwurru-jaru Aboriginal Corporation, 2002

- McConvell, P. "Changing places: European and Aboriginal styles," in Hercus, L., Hodges, F. and Simpson, J. (eds.,). The land is a map: Placenames of indigenous origin in Australia. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics and Pandanus Press, 2002, pp. 50-61

- McConvell, P. "Linguistic stratigraphy and native title: the case of ethnonyms," in Henderson, J. and Nash, D. (eds.,). Language in native title [Native Title Research Series]. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press, 2002, pp. 259-290

- McConvell, P. "Mix-im-up speech and emergent mixed languages in Indigenous Australia," in Texas Linguistic Forum [Proceeedings from the Ninth Annual Symposium about Language and Society - Austin April 20-22, 2001] 44, 2001, pp. 328-349

- McConvell, P. "Gurindji," in Dixon, R. M. W. and Blake, B. J. (eds.,). The handbook of Australian Languages Vol. 5. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000

- McConvell, P. "Ergativity and the scope of 'again' in English and Gurindji." Copenhagen, Functional Grammar Conference, 1990

- McConvell, P. "Mix-im-up: Aboriginal code-switching, old and new," in Heller, M. (ed.,). Codeswitching: anthropological and sociolinguistic perspectives. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 1988, pp. 97-150

- McConvell, P. "Nasal Cluster Dissimilation and constraints on phonological variables in Gurindji and related languages," in Evans, N. and Johnson, S. (eds.,). Aboriginal Linguistics 1. Armidale: Department of Linguistics, University of New England, 1988, pp. 135-187

- McConvell, P. "The Origins of Subsections in Northern Australia," in Oceania 56, 1985, pp. 1-33

- McConvell, P. "Domains and codeswitching among bilingual Aborigines," in Clyne, Michael (ed.,). Australia, meeting place of languages. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. Series C - No. 92, 1985, pp. 95-125

- McConvell, P. "Hierarchical variation in pronominal clitic attachment in the Eastern Ngumbin languages," in Rigsby, B. and Sutton, P. (eds.,). Papers in Australian Linguistics No.13: Contributions to Australian Linguistics. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics, 1980, pp. 31-117

-

Gurindji Kriol

Language change and formation

(excerpt from McConvell, Patrick and Meakins, Felicity. "Gurindji Kriol: A Mixed Language emerges from Code-switching," in Australian Journal of Linguistics 25(1), 2005, pp. 9-30)

Gurindji Kriol is the main language of Kalkaringi and Dagaragu, twin communities situated 460km south west of Katherine in the north of Australia. It arose from contact between white pastoralists who spoke English, and the Gurindji, the traditional owners of the country the pastoralists colonised. After the initial conflict period in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many Gurindji people worked on the cattle stations as kitchen hands and stockman. The lingua franca between the two groups was an English-creole, Kriol. The Gurindji, who already spoke a number of the related neighbouring languages added Kriol to this repertoire and their code-switching practices. Nowadays all Gurindji people speak Gurindji Kriol, older people also speak Gurindji and younger speakers have a reasonable passive knowledge of Gurindji. Gurindji is an endangered language, with only 60 speakers remaining in 2003. Gurindji Kriol is the language transmitted to the new generation at present.

Some socio-historical evidence might be relevant as to why full language shift did not take place, as it has done in other areas in northern Australia. In 1966 the Gurindji went on strike from the cattle stations where they had worked and the long-standing dispute over wages and conditions revealed itself as a struggle for land rights. 1975 saw the hand back of traditional lands to the Gurindji by the then Australian Prime Minister, Gough Whitlam, a highly significant step for post-colonial law and history and for the Gurindji themselves. It is possible that the pride associated with these momentous events and the resultant desire to mark Gurindji identity linguistically may have affected the course of language shift and motivated the maintenance of a mixed language.

Typology

(excerpt from McConvell, Patrick and Meakins, Felicity. "Gurindji Kriol: A Mixed Language emerges from Code-switching," in Australian Journal of Linguistics 25(1), 2005, pp. 9-30)

Typologically, Gurindji Kriol exhibits a split between the verbal and nominal systems as do other mixed languages like Michif. In Gurindji Kriol, basic verbs such as go and sit, the tense-aspect-mood system and transitive morphology are derived from Kriol, whereas emphatic pronouns, possessive pronouns, case markers and nominal derivational morphology have been transplanted from Gurindji relatively intact, but with some innovations . Demonstratives, nouns, verbs and adpositions are adopted from both languages, however some generalisations can be made about their distribution. A short excerpt of a GK story which demonstrates some of these features is below (1). Gurindji elements are in italics:

nyawa-ma wan karu bin plei-bat pak-ta nyanuny warlaku-yawung-ma.

this-TOP one child PST play-CONT park-LOC 3sg.DAT dog-HAVING-TOP

'This one kid was playing at the park with his dog.'tubala bin pleibat. i bin tokin la im

2pl PST PST play. 3sg PST talk PREP 3sg

'The two of them were playing and the kid said to him:'"kamon warlaku partaj ngayiny leg-ta ..."

come.on dog go.up 1sg.DAT leg-LOC

'Come on dog jump up on my leg …'"ngali pleibat nyawa-ngka."

1plu.inc play this-LOC.

"We'll play here."References

- McConvell, P. and Meakins, F. "Gurindji Kriol: A Mixed Language emerges from Code-switching," in Australian Journal of Linguistics 25.1, 2005, pp. 9-30

- Meakins, F. and O'Shannessy, C. "Possessing variation: Age and inalienability related variables in the possessive constructions of two Australian mixed languages," in Monash Papers in Linguistics 4.2, 2005, pp. 43-63

- Charola, Erika. The Verb Phrase Structure of Gurindji Kriol. Unpublished honours thesis. The University of Melbourne, 2002

- McConvell, P. "Mix-im-up speech and emergent mixed languages in Indigenous Australia," in Texas Linguistic Forum [Proceeedings from the Ninth Annual Symposium about Language and Society - Austin April 20-22, 2001] 44, 2001, pp. 328-349

- Dalton, L., Edwards, S., Farquharson, R., Oscar, S. and McConvell, P. "Gurindji children's language and language maintenance," in International Journal of the Sociology of Language 113, 1998, pp. 83-96

- McConvell, Patrick. "Discourse frame analysis of code-switching," in Gorter, D. and Piebenga, A. (eds.,). Code-switching: papers from the Leeuwarden Summer School 1994. Network on Language Contact and Codeswitching, 1994

- McConvell, P. "Mix-im-up: Aboriginal code-switching, old and new," in Heller. M. Codeswitching: anthropological and sociolinguistic perspectives. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 1988, pp. 97-150

- McConvell, P. "Domains and codeswitching among bilingual Aborigines," in Clyne, Michael. Australia, meeting place of languages. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. Series C - No. 92, 1985, pp. 95-125

-

Kriol

Language situation

The varieties of English spoken in Tennant Creek can best be characterised on a continuum, ranging from heavily creolised English (CE) at one end, to light Aboriginal English (AE), close to standard Australian English (SAE) at the other. The variety a speaker uses depends on the situation, interlocutors present and the varieties that a speaker has in their repertoire. Speakers generally use very light Aboriginal English in interactions with Non-Indigenous people. Standard Australian English (SAE) is the language of education and institutions. Through media such as television, videos and popular music, people hear SAE and other varieties of English.

Some speakers use Aboriginal English most of the time, but include some features of creolised English in interactions with speakers whose style is generally heavier. In some speech networks, heavily creolised English is the code of in group comunication. Given that these varieties exist in the speech community of Aboriginal people in Tennant Creek, there is great variablity. A single stretch of discourse may include features from lighter and heavier ends of the continuum. These sub-systems do not appear to operate independently in speaker useage.

Speakers also use items from Warumungu, such as lexicon, some verbs and nominal morphology. Older people tend to be full speakers of Warumungu, while most people under 40 years of age are partial speakers and so their use of Warumungu is always within otherwise CE or AE discourse.

Typology

Sound system

The phonology of heavily creolised English is influenced by Indigenous languages. Affricates and fricatives, which appear in English only, are generally replaced by corresponding stops. Consonant clusters are separated with a weak vowel. Dipthongs alternate with short clear vowels. The phonology of Aboriginal English is closer to English, though features mentioned in heavily creolised English appear.

Verb phrase

Word order in Aboriginal English and creolised English is SVO, though the object may be moved to clause initial position, for topicalisation.

An object pronoun referent may also be topicalised with a postposed referential noun phrase.

Transitivity is marked on verbs with the suffix -im.

1) Jangay dei gatim.

Shanghay(s) they have.

2) Dei bin gitim im, nunuwan babiwan.

They got it, (the) little baby (bird)

If reference is made to an event that occurred prior to the time of speaking verbal auxillary 'bin' can be used with a verbal element . For future or potential state, garra, gata tends to be used with verbal element.

3) An nyili garra pokim im na.

And ( the) prickle is going to poke him (he going to step on the prickle)

Progressive aspect is indicated by the suffix - in, ing.

4) Oni wanbala running na.

Only one (person) is running now

Durative and iterative aspect is indicated by the suffix -bat, or -abat, which Sandefur (1991), discussing Kriol spoken to the north of the Tennant Creek region, claims has an overlap in meaning with the progresssive, and an interweaving of distribution and co-occurrence. The iterative meaning of -bat is more common than the durative meaning and can either refer to repetition of an action or plurality of participants. The iterative aspect is associated with creolised English, as it tends to occur more frequently in this speech style.

5) Tubla bin jasimbat dat julaka.

They (2) were chasing that bird

6) "Maami, dei bin bildimabat mi".

"Mummy, they were beating me"

Verbless clauses are used to describe states perceived as existing at the time of speaking.

7) Dis imkay karnanti.

This (is) his mother

8) Dei brabli cruel.

They are very cruel.

9) Weya im na? weya im kina?

Where (is) he now? where (is) he (going)

Noun phrase Nouns need not be marked for number or definiteness in AE and CE, (see examples 1,2,3, 5) but determiners can be used to express these.

(10) Tribala kartti bin jasimbat.

Adjectives generally appear with the nominalising suffix -wan (example 2), and in the case of numerals -bala (example 10)

References about Kriol in general

- Munro, J. Substrate language influence in Kriol: The application of transfer constraints to language contact in northern Australia. Unpublished PhD, University of New England, Armidale, 2005

- Harris, J. "Kriol - The creation of a new language," in Romaine, S. (ed.,). Language in Australia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004

- Mühlhaüsler, P. "Overview of the pidgin and creole languages of Australia," in Romaine, S. (ed.,). Language in Australia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004

- Sandefur, J. "A sketch of the structure of Kriol," in Romaine, S. (ed.,). Language in Australia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004

- Meyerhoff, M. "Transitive marking in contact Englishes," in Australian Journal of Linguistics 16, 1996, pp. 57-80

- Rhydwen, M. Writing on the backs of blacks: Voice, Literacy and community in Kriol fieldwork. Brisbane: University of Queensland Press, 1996

- Harris, J. "Losing and gaining a language: The story of Kriol in the Northern Territory," in Walsh, M. and Yallop, C. (eds.,). Language and culture in Aboriginal Australia. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press, 1993

- Graber, P. "Kriol in the Barkly Tableland," in Australian Aboriginal Studies 2, 1987, pp. 14-19

- Graber, P. "The Kriol particle 'na'," in Working papers in language and linguistics 21, 1987, pp. 1-21

- Marret, M. "Kriol and literacy," in Australian Aboriginal Studies 2, 1987, pp. 69-70

- Sandefur, J. "Mission life, mission education and the rise of creole language," in Journal of Christian Education 85, 1986, pp. 23-34

- Harris, J. Northern Territory pidgins and the origin of Kriol. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics, 1986

- Sandefur, J. and Harris, J. "Variation in Australian Kriol," in Fishman, J. (ed.,). The Fergusonian impact. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 1986, pp. 180-190

- Harris, J. and Sandefur, J. "Kriol and multilingualism," in Clyne, M. (ed.,). Australia, meeting place of languages Vol. 92. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics, 1985, pp. 257-264

- Sandefur, J. "Dynamics of an Australian creole system," in Pacific Linguistics A 72, 1985, pp. 195-214

- Sandefur, J. "Aspects of the socio-political history of Ngukurr (Roper River) and its effects on language change," in Aboriginal History 1-2, 1985, pp. 205-219

- Sandefur, J. A language coming of age: Kriol of North Australia. Unpublished MA Thesis, University of Western Australia, Perth, 1984

- Harris, J. and Sandefur, J. "The Creole language debate and the use of creoles in Australian schools," in The Aboriginal Child at School 12(1), 1984, pp. 8-29

- Sandefur, J. "A resource guide to Kriol," in Sandefur, J. (ed.,). Papers on Kriol Vol. 10. Darwin: SIL, 1984, pp. 107-140

- Hudson, J. Grammatical and semantic aspects of Fitzroy Valley Kriol. Darwin: SIL, 1983

- Harris, J. and Sandefur, J. "Creole languages and the use of Kriol in Northern Territory schools," in Unicorn 9(3), 1983, pp. 249-264

- Hudson, J. "Transitivity and aspect in the Kriol verb," in Papers in pidgin and creole linguistics: Pacific Linguistics A-65 3, 1983, pp. 161-175

- Sandefur, J. "Kriol and the question of decreolisation," in International Journal of the Sociology of Language 36, 1982, pp. 5-13

- Sandefur, J. "When will Kriol die out?" in MacKay, G. A. and Sommer, B. A. (eds.,). Application of linguistics to Australian Aboriginal contexts (ALAA Occasional Papers). Melbourne: Melbourne University, 1982, pp. 34-43

- Sandefur, J. "Kriol: An Aboriginal language," in Hemisphere 25, 1981, pp. 252-256

- Sandefur, J. "Kriol: Language with a history," in Northern Perspective 4(1), 1981, pp. 3-7

- Sandefur, J. "The stepchild who began Cinderella: Pidgin English comes into its own," in On Being 8(8), 1981, pp. 43-45

- Sandefur, J. "An introduction to conversational Kriol," in Working papers of SIL - AAIB Series B. Darwin: SIL, 1981

- Hudson, J. Fitzroy Valley Kriol wordlist. Unpublished manuscript, 1981

- Rumsey, A. On some syntactico-semantic consequences of homophony in northwest Australian Pidgin/Creole English. Unpublished manuscript, 1981

- Meehan, D. Kriol literacy: Why and how ... Notes on Kriol and the Bamyili school bilingual education program. Barunga, N. T.: Bamyili Press, 1980

- Capell, A. "Languages and creoles in Australia," in Sociologia Interationalis 17, 1979

- Murtagh, E. Creole and English Used as Languages of Instruction with Aboriginal Australians. Stanford University, 1979

- Sandefur, J. An Australian creole in the Northern Territory: A description of Ngukurr-Bamyili dialects (Part 1). Darwin: SIL, 1979

- Steffensen, M. "Reduplication in Bamyili Creole," in Papers in Pidgin and Creole Linguistics No. 2. Pacific Linguistics A57, 1979, pp. 119-133

- Davidson, G. A preliminary report on traditional culture learning and Aboriginal pidgin as part of the school's bilingual program at Bamyili, N.T. Unpublished manuscript, Canberra, 1977

- Fraser, J. "A phonological analysis of Fitzroy Crossingchildren's pidgin," in Hudson, J. (ed.,). Five Papers in Australian Phonologies: Work papers SIL-AAB A.1. Darwin, 1977, pp. 145-204

- Fraser, J. A tentative short dictionary of Fitzroy Crossing children's pidgin. From data collected Oct-Nov 1974; revised March 1977.Unpublished manuscript, Darwin, 1977

- Hudson, J. Some common features in Fitzroy Valley Kriol, 1977

- Sharpe, M. and Sandefur, J. "A brief description of Roper Creole," in Brumby, E. and Vaszolyi, E. (eds.,). Language problems and Aboriginal education. Mt Lawley: College of Advanced Education, 1977, pp. 51-60

- Steffensen, M. A description of Bamyili creole.Unpublished manuscript, Urbana, Illinois, 1977

- Steffensen, M. "Double talk: When it means something and when it doesn't," in Papers from the 13th Regional Meeting, Chicago Linguistic Society, 1977, pp. 603-611

- Thompson, H. Creole as the vernacular language in a bilingual program at Bamyili school in the Northern Territory. Torrens College of Advanced Education, Adelaide, 1976

- Steffensen, M. Bamyili creole. Unpublished manuscript, Madison, Wisconsin, 1975

- Richards, E. and Fraser, J. "A comparison and contrasting of the noun phrases of Walmatjari with the noun phrases of Fitzroy Crossing children's pidgin," Paper presented at the ALS 7, Sydney, 1975

- Sharpe, M. "Report on Roper Pidgin and the possibility of its use in a bilingual program," in Report on the Third Meeting of the Bilingual Education Consultative Committee held in Darwin on 27-29 November 1974. Darwin: Department of Education, 1974

- Hall, R. A. "Notes on Australian Pidgin English," in Language, 19, 1943, pp. 263-267

-

Warlmajarri

Language situation

(the following sketch of the phonology and grammar of the language is from the Walmajarri - English Dictionary compiled by Eirlys Richards and Joyce Hudson)

The Walmajarri people traditionally lived in the Great Sandy Desert to the south of the Kimberley. Subsequent events took them to cattle stations, towns and missions scattered over a wide area. Today, communities with substantial Walmajarri population are:

Bayulu (Gogo), Bidyadanga (La Grange), Djugerari (Cherrabun), Junjuwa (Fitzroy Crossing), Looma, Millijidee, Mindibungu (Bililuna), Mindi Rardi (Fitzroy Crossing), Mulan (Lake Gregory), Ngumban (Pinnacles), Ngalapita, Ngurtawarta, Wangkajungka (Christmas Creek),Yagga, Yakanarra (Old Cherrabun) - the redrawn boundary now means Yakanarra is located on Gogo, Yungngora (Noonkanbah).

Typology

There are seventeen consonants and six vowels, three long and three short. The charts below show how the various sounds are made:

Walmajarri consonants

1 both lips

2 tongue tip behind teeth

3 tongue tip turned back

4 tongue blade on hard palate

5 back of tongue on back of palate

1 air stream completely stopped

p

t

rt

j

k

2 air stream through nose

m

n

rn

ny

ng

3 air stream around sides of tongue

l

rl

ly

4 air stream restricted over centre of tongue

rr

5 air stream unrestricted

w

y

r

Walmajarri vowels

tongue in front of mouth

tongue at centre of mouth

tongue at back of mouth

tongue high in mouth

short

long

i

ii

u

uu

tongue low in mouth

short

long

a

aa

Verbal auxiliary

There is no equivalent in English to the Walmajarri verbal auxiliary. The two purposes of the verbal auxiliary are:

- to show which person or thing or how many persons or things were involved in the action. There is no distinction between masculine and feminie so where English distinguishes between he, she and it, Walmajarri does not

- to show the mood of the sentence. For instance, if the boy (1 person) does something TO the girl (1 person), the verbal auxiliary has the form pa. If the boy (1 person) does something FOR the girl (1person) the verbal auxiliary is parla. If the boy (1 person) ACCOMPANIES the girl (1 person) the verbal auxiliary is manyanta. If other people are involved the verbal auxiliary changes to indicate this.

With so much information contained in the verbal auxiliary, the sentence can be reduced to two words. The verb tells what the action was and the verbal auxiliary tells who or what was involved in the action. These two words form a mini-sentence.

Yani manyanta went he-with him 'He went with him/her' Nyanya palupinya saw they-pl them 2 They (3 or more) saw them (2) Cases

In a Walmajarri sentence the words can be moved about fairly freely, unlike English which requires a fixed word order to maintain the same meaning, eg in the sentence 'The girl saw the boy', a change of order makes a new sentence with a different meaning, 'The boy saw the girl'. Walmajarri word order is more free because where English uses word order and prepositions to indicate relationships between words in a sentence, Walmajarri uses suffixes.

There are two types of cases in Walmajarri. One group is shown on the verbal auxiliary as well as on the nominal, ie they are cross referenced [Ergative, Accessory, Dative]. The other group is only shown on the nominal (Locative, Purposive, Preventative, Allative, Ablative, Consequent, Manner).

Nominals

The term nominal is used Walmajarri for word that potentially take the case suffixes. Most of these words would be clearly classified in English as nouns or adjectives. In Walmajarri this distinction is not clear because adjectives often take the place of nouns.

Manga purlka [kirta(E)] pirriyani

girl big came

'The big girl came.'

Purlka [kirta(E)] pirriyani

'The big (girl) came.'

The form without the noun is used unless there is need to be specific about the person involved.

Verbs

The verb consists of a stem and four orders of suffixes. Stems may be monomorphemic or compound and are divided into five conjugation classes. Before tense suffixes can be added to the verb, the mood of the sentence has to be known. This is because there are two sets of suffixes, based on the Realis-Irrealis distinction. When the mood is indicative, interrogative or hortatory, the Realis Tense System applies. When the mood is intentive, admonitive, imperative, negative, prohibitive or inabilitative the Irrealis Tense System applies. In finite verbs the Realis Tense System makes four distinctions: past, customary and future, with present only in the repetiitive/continuous aspect. The Irrealis tense System distinguishes only two, past and non-past. The two infinite forms are non-past (infinitive) and past. The past expresses an action prior to that of the main verb.

Kamparnu-rla marna ngarni.

cook-past I ate

'After cooking it I ate it.'

The non-past is the infinitive to which the suffixes are added.

Kiy [Kuyu(E)] kamparnu-jangka marna ngarni.

meat cook-from I ate

'I ate the cooked meat.'

(Richards, Eirlys and Hudson, Joyce. Walmajarri-English dictionary. Darwin: SIL, 1990)

References

- Richards, Eirlys and Hudson, Joyce. Walmajarri-English dictionary. Darwin: SIL, 1990

- Richards, Eirlys. "The Walmajarri noun phrase," in Work Papers of SIL-AAB, A:3, 1979, pp. 93-127

- Hudson, Joyce. The core of Walmatjari grammar. Canberra: A.I.A.S, 1978

- Hudson, Joyce and Richards, Eirlys et al. "The Walmatjari: an introduction to the language and culture," in Work Papers of SIL-AAB, B:1, 1978

- Hudson, Joyce and Richards, Eirlys. "The phonology of Walmatjari," in Oceanic Linguistics 8:2, 1969, pp. 171-89

-

Warumungu

Language situation

Warumungu speakers live at Tennant Creek, to the north and east at Elliott, Marlinja, Kurnturlpara, Ngurrara, Wogayala, and Alroy Downs, and on several outstations such as Likarrapartta, Jurntu Jungu, Pingala, and to the south at Kurraya, Alekarenge, Karlinjarangi, and Jungkkaji. In most of these communities other languages are spoken.

In the mid 1990s Robert Hoogenraad surveyed the languages of the Barkly area, and estimated that there were then about 700 people who could speak some Warumungu. While older people can speak Warumungu fluently, very few children and teenagers have spoken it regularly since at least the early 1980s.

Warumungu was profiled in The Federation of Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Languages and Culture (FATSIL) newsletter "Voice of the Land"

Language work on Warumungu is carried on in Tennant Creek through the Papulu Apparr-kari Aboriginal Corporation, as well as in the Nyinkka Nyunyu Aboriginal Art and Cultural Centre.

Typology

Warumungu has been classified as a subgroup on its own within the Western Desert type of Pama-Nyungan languages by Oates (1975: I, 145). According to this classification, Warumungu would be more closely related to Warlpiri and Warlmanpa, than, say, to Arandic. However,in the classification of O'Grady, Voegelin and Voegelin (1966, p.42), Warumungu is coordinate with the Wakayic group, the Arandic group and the South-West group to which Mudbura, Warlpiri and Warlmanpa belong. Its exact genetic relationship to these languages is still uncertain.

Phonologically, the presence of two stop series sets Warumungu apart from neighbouring languages.

There are five places of articulation for stops and nasals: bilabial, apico-alveolar, apico-postalveolar (retroflex), lamino-palatal and velar. There are three laterals, one tap r and three semivowels (including a retroflex glide r). There are three vowels. Vowel length is distinctive in initial syllables. Primary stress occurs word-initially. The most striking phonological rules are alternations in consonant length and voicing, and vowel deletion, which deletes the first of two adjacent vowels across word boundaries.

Warumungu is a suffixing language. Grammatical functions are expressed by Ergative-Absolutive case-marking. Word order is used for information structure purposes. Initial and second position are particularly salient. Pronouns appear in clusters, marking either one pronominal argument (intransitive subject) or two (transitive subject and direct, reflexive or indirect object). They normally appear in initial position, or encliticised to a constituent in initial position. Verb roots are a small closed class. Complex verbs are created by compounding these verb roots with preverbs, which appear to be an open class. There is no evidence for a surface verb phrase, but nouns and their modifiers do appear to form phrases.

People

Main investigators

Dr Patrick McConvell

Research Fellow, Linguistics; College of Arts and Social Sciences

Dr Patrick McConvell has worked on Australian Indigenous languages, especially in the west of the Northern Territory and the Kimberleys and Pilbara of Western Australia. Apart from grammar and dictionary work he is interested in the maintenance of languages, and in the shift to Kriol, code-switching and mixing of languages. He has been involved with the setting up of the Kimberley Language Resource Centre, and training of Indigenous language workers at Batchelor Institute. Dr McConvell has taught linguistic and social anthropology and has a major interest in the relationship between language, society and culture.

Apart from ACLA, his current research interests are: Gurindji Grammar and Dictionary compilation, linguistic prehistory of Australia and investigating the past with the aid of linguistic evidence, and traditional relationships to land in the Victoria River District NT and North Queensland.

Email: patrick.mcconvell@anu.edu.au

List of Publications

Professor Jane Simpson

Linguistics, Head of

School of Language

Studies, ANU College

of Arts and Social

Science

Professor Jane Simpson has worked on one of the languages in the study, Warumungu, since 1979, and have been involved in language maintenance work in the Tennant Creek area. She has also studied historical records to determine the development of pidgins in different parts of Australia.

Professor Simpson became involved in the project, partly because she wanted to find out more about the conditions that favour maintenance of traditional languages, but also because she want to understand the ways in which learners reinterpret the data they hear in producing creoles and new mixed languages.

Professor Jill Wigglesworth

Linguistics, School of

Languages and

Linguistics, the University

of Melbourne

Gillian Wigglesworth received her PhD in 1993 from La Trobe University with a thesis entitled "investigating children's cognitive and linguistic development through narrative". From 1992 to 1994 she worked at the University of Melbourne in the Department of Applied Linguistics and the Language Testing Research Centre, where she focussed particularly on the development of oral language assessments. She worked in the Department of Linguistics at Macquarie University from 1995-2001 where she was coordinator of the applied linguistics postgraduate programs. From 2000-2001 she was also a member of the Adult Migrant English Program Research Centre research staff. She returned to the University of Melbourne in 2001. Her research interests include first and second language acquisition, language testing and evaluation and bilingualism, using both quantitative and qualitative approaches to data collection and analysis.

Research assistants and PhD graduates

Dr Samantha Disbray

Dr Samantha Disbray has worked as a linguist in Central Australia since 1998, with Centre for Australian Languages andLinguistics at Batchelor Institute of Indigenous Tertiary Education and for the Institute for Aboriginal Development (IAD), training Indigenous Language Workers in English and vernacular literacy and language research, before becoming a researcher for the Aboriginal Child Language Acquisition Project (ACLA) (2004-2007). She completed her PhD at the University of Melbourne in 2008, with a dissertation on the development of children's discourse skills in a contact variety, Wumpurrarni English. After completing the ACLA project, Dr Disbray took the position of regional Linguist with the Northern Territory Department of Education, providing professional learning and support to teachers of Indigenous languages and English as an additional language or dialect. Since 2013 she has been a Senior Research Fellow at The Northern Institute, Charles Darwin University, working on the Remote Education Project.

Her research interests are Indigenous Languages - traditional and contemporary in remote Australia, the provision of education to remote school in Northern Australia and the Northern Territory Bilingual Education Program.

Email: samantha.disbray@cdu.edu.au

Associate Professor Felicity Meakins

Dr (now Associate Professor) Felicity Meakins worked as a community linguist at Diwurruwurru-jaru Aboriginal Corporation (Katherine Regional Aboriginal Language Centre) between 2001-04. She joined the Aboriginal Child Language project (University of Melbourne) in 2004 as a PhD student. She completed her PhD in 2008 and continued documenting Gurindji, Bilinarra and Gurindji Kriol as a part of the Jaminjungan and Eastern Ngumpin DOBES project and then with an ELDP grant at the University of Manchester. Dr Meakins currently holds an ARC grant looking at the contact process which went into the formation of Gurindji Kriol.

She is the author of Case-Marking in Contact (Benjamins, 2011), Bilinarra to English Dictionary (Batchelor Press, 2013) and a co-author of A Grammar of Bilinarra (Mouton, 2013, with Rachel Nordlinger), Gurindji to English Dictionary (Batchelor Press, 2013 with Patrick McConvell, Erika Charola, Norm McNair, Helen McNair and Lauren Campbell) and Bilinarra, Gurindji and Malngin Plants and Animals (LRM, 2012 with Glenn Wightman).

Weblink: Associate Professor Felicity Meakins web page

Email: f.meakins@uq.edu.au

Dr Karin Moses

Karin Moses, who conducted the research at Yakanarra, first worked in an Aboriginal Community in 1988 when she was appointed to the position of post primary teacher at Kulkarriya, the independent school at Noonkanbah. She has also worked as a lecturer for Batchelor College in what was then known as the Remote Teacher Education Programme, firstly in Tennant Creek and then at Yirrkala. Karin completed a Masters in Applied Linguistics in 1995; her thesis focused on the interaction between the bilingual children and their monolingual teacher in a small Alyawarr community at Epenarra.

Her interest in this project stemmed from her concern about the way in which mainstream pedagogical language use and practice disadvantaged Aboriginal children. Although research into classroom practice and the Aboriginal child has been conducted over a number of years now, very little is based on a detailed study of Aboriginal language use; even less is based on data that focuses on pre-school Aboriginal children's language use.

This project provides an exciting opportunity to understand something about the way in which Aboriginal people at three different locations use language with their small children and how these children become accomplished language users themselves. Such an insight into language practice could contribute much to our knowledge about the relationship between language and learning, and could have implications for improved teaching practice.

Email: k.moses@latrobe.edu.au

Professor Carmel O'Shannessy

O'Shannessy

Professor Carmel O'Shannessy is an Assistant Professor in Linguistics at the University of Michigan. Her PhD is from the University of Sydney and the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, The Netherlands. She has been involved with Lajamanu Community since 1998, first working in the Two-way Learning program in the school (1998-2001), and since then visiting annually for research. Before going to Lajamanu Community she spent two years in a Kriol-speaking community, Ngukurr, as a lecturer with Batchelor Institute of Indigenous Tertiary Education (BIITE), working in teacher education (1996-7). She was an ESL and elementary school teacher for several years prior to that.

In her research she examines the complex linguistic situation in Lajamanu Community from multiple perspectives, including the children's acquisition of multiple codes, differences in speech styles across ages, documentation of Light Warlpiri, and of traditional Warlpiri songs. Light Warlpiri is a mixed language, a type that occurs rarely, and it has some unique features, specifically innovative structures in the verbal auxiliary system. The similarities and differences between Warlpiri and Light Warlpiri are especially interesting, as is the way in which Light Warlpiri is developing.

For more details about her research please see the Carmel O'Shannessy web page.

Email: carmelos@umich.edu

Publications

Books and journal articles

2013

- Disbray, S. and Loakes, D. "Writing Aboriginal English & Creoles: Five case studies in Australian education contexts," in Kids, Kriols and Klassrooms. Special Edition, Australian Review of Applied Linguistics, November 2013

- Meakins, F. and Wigglesworth, G. "How much input is enough? Correlating comprehension and child language input in an endangered language," in Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 34(2), 2013, pp. 171-188

2012

- Loakes, D., Moses, K., Simpson, J. and Wigglesworth, G. "Developing tests for the assessment of traditional language skill: A case study in an Indigenous Australian community," in Language Assessment Quarterly 9(3). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2012, pp. 311-330

- Meakins, F. "Which Mix? - Code-switching or a mixed language - Gurindji Kriol," in Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages, 27(1), 2012, pp. 105-140

2011

- Meakins, F. Case marking in contact: The development and function of case morphology in Gurindji Kriol. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 2011

2010

- Meakins, F. and O'Shannessy, C. "Ordering arguments about: Word order and discourse motivations in the development and use of the ergative marker in two Australian mixed languages," in Lingua, 120(7), 2010, pp. 1693-1713

2009

- Meakins, F. "The case of the shifty ergative marker: A pragmatic shift in the ergative marker in one Australian mixed language," in Barddal, J. and Chelliah, S. (eds.,). The Role of Semantics and Pragmatics in the Development of Case. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 2009, pp. 59-91

2008

- Disbray, S. "Story-telling Styles: a study of adult-child interactions in Tennant Creek," in Simpson, J. and Wigglesworth, G. (eds.,). Children's Language and Multilingualism. London, New York: Continuum International Publishing Group, 2008, pp. 45-65

- Disbray, S. and Wigglesworth, G. "A longitudinal study of language acquisition in Aboriginal children in three communities," in Robinson, G., Eichelkamp, U., Goodnow, J. and Katz, I. (eds.,). Contexts of Child Development: Culture, Policy and Intervention. Darwin: Charles Darwin University Press, 2008, pp. 167-182

- Meakins, F. "Unravelling languages: Multilingualism and language contact in Kalkaringi," in Simpson, J. and Wigglesworth, G. (eds.,). Children's language and multilingualism: Indigenous language use at home and school. New York: Continuum, 2008, pp. 247-264

- Meakins, F. "Land, language and identity: The socio-political origins of Gurindji Kriol," in Meyerhoff, M. and Nagy, N. (eds.,). Social Lives in Language. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 2008, pp. 69-94

- Morrison, B Nakamarra and Disbray, S. "Warumungu children and language in Tennant Creek." Warra wiltaniappendi = Strengthening languages. Proceedings of the Inaugural Indigenous Languages Conference (ILC) 2007, Adelaide, Australia, 2008, pp. 107-111

- O'Shannessy, Carmel. "Children's production of their heritage language and a new mixed language," in Simpson, Jane and Wigglesworth, Gillian (eds.,). Children's Language and Multilingualism. London, New York: Continuum International Press, 2008, pp. 261 - 282

2005

- Disbray, S. (compiler) with Warumungu speakers from the Tennant Creek Community. Warumungu Picture Dictionary. Alice Springs: IAD Press, 2005, pp. 1-176

- Disbray, S. and Simpson, J. "The expression of possession in Wumpurrarni English, Tennant Creek," (7.21Mb pdf) in Monash University Working Papers in Linguistics 4(2), 2005, pp. 65-86

- McConvell, Patrick and Meakins, Felicity. "Gurindji Kriol: A mixed language emerges from code-switching," (115kb pdf) in Australian Journal of Linguistics 25.1, 2005, pp. 9-30

- McConvell, Patrick. "Language contact interaction and possessive variation," (6.59Mb pdf) in Monash University Working Papers in Linguistics 4.2, 2005, pp. 87-105

- Meakins, F. and O'Shannessy, C. "Possessing variation: Age and inalienability related variables in the possessive constructions of two Australian mixed language," (6.78Mb pdf) in Monash University Linguistics Papers 4(2), 2005, pp. 43-63

- O'Shannessy, Carmel. "Light Warlpiri: A new language," (140kb pdf) in Australian Journal of Linguistics 25.1, 2005, pp. 31-57

2004

- Hughes, B., Penton, D., Bird, S., Bow, C., Wigglesworth, G., McConvell, P. and Simpson, J. "Management of metadata in linguistic fieldwork - Experience from ACLA." Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation. European Language Resources Association: Paris, 2004, pp. 193-196

PhD theses

2009

- Disbray, S. More than one way to catch a frog: Children's discourse in a contact setting. Unpublished PhD dissertation, The University of Melbourne, 2009. Available online on The University of Melbourne Library Digital Repository.

- Moses, K. Do dinosaurs hug in the Kimberley? The use of questions by Aboriginal caregivers and children in the Kimberley. Unpublished PhD dissertation, The University of Melbourne, 2009. Available through The University of Melbourne Library catalogue.

2007

- Meakins, F. Case-marking in contact: the development and function of case morphology in Gurindji Kriol, an Australian mixed language. Unpublished PhD dissertation, The University of Melbourne, 2007. Available through The University of Melbourne Library catalogue.

Selected conference papers (2004-2006)

2006

- McConvell, Patrick and Simpson, Jane. "The transitive marker-im in Australian Indigenous English, creoles and hybrid languages: variation and change." Paper given at Blackwood by the Beach. Pearl Beach, Sydney 17-19 March 2006

- Disbray, Samantha. "The expression of location in Wumpurrarni English." Paper given at Blackwood by the Beach. Pearl Beach, Sydney 17-19 March 2006

- O'Shannessy, Carmel and Meakins, Felicity. "Comprehending Ergative Marking and Word Order in Light Warlpiri and Gurindji Kriol." Paper given at Blackwood by the Beach. Pearl Beach, Sydney 17-19 March 2006

2005

- McConvell, Patrick and Meakins, Felicity. "The Animacy dimension in the reshaping of ergative case marking in Gurindji Kriol, an Australian mixed language." Paper given at Pionier Colloquium on Animacy. Radboud University, Holland 19-20 May 2005

- McConvell, Patrick, Meakins, Felicity and O'Shannessy, Carmel. "Kriol and mixed languages in Australia: constraining substrate and superstrate explanations of emergent structures." Paper given at Creoles Conference. MPI Leipzig, Germany 3-5 June 2005

- Disbray, Samantha. "Language Mixing and Language Maintenance: Story telling strategies among Aboriginal caregivers." Paper given at IASCL Congress. Berlin 25-29 July 2005

- Wigglesworth, Gillian and Disbray, Samantha. "A Longitudinal Study of Language Acquisition in Australian Aboriginal Children in Three Communities." Paper given at Imagining Childhood: Children, Culture and Community. CDU, Alice Springs 20-22 Sept 2005

2004

- Disbray, Samantha and Wigglesworth, Gillian. "Emergent literacy practices in pre-school age indigenous children in Tennant Creek." Paper given at the Australian Linguistics Society Conference. Sydney, Australia 13-15 July 2004; and the Australia Applied Linguistics Association Conference. Adelaide 15-17 July 2004

- Meakins, Felicity and O'Shannessy, Carmel. "Shifting functions of ergative case-marking in Light Warlpiri and Gurindji Kriol." Paper given at the Australian Linguistics Society Conference. Sydney, Australia 13-15 July 2004

- McConvell, Patrick, Meakins, Felicity and O'Shannessy, Carmel. "Emergent Possessive Constructions in Light Warlpiri and Gurindji Kriol." (45kb pdf) Paper given at the Language Contact, Hybrids and New Varieties Symposium. Monash University, Melbourne, Australia 3-4 Sept 2004

- Simpson, Jane and Disbray, Samantha. "Evolving Ways of Expressing Possession in the Tennant Creek Area." (20kb pdf) Paper given at the Language Contact, Hybrids and New Varieties Symposium. Monash University, Melbourne, Australia 3-4 Sept 2004

- Disbray, Samantha, McConvell, Patrick, Meakins, Felicity, Moses, Karin, O'Shannessy, Carmel, Simpson, Jane and Wigglesworth, Gillian. "Language Acquisition by Aboriginal Children and Educational Implications." (4Mb pdf) Paper given at AIATSIS. Canberra, Australia 18 Oct 2004

Regions

Kalkaringi and Dagaragu

1. History

1. History excerpt from McConvell, P. "Gurindji," in Dixon, R. M. W. and Blake, B. J. (eds.,). The Handbook of Australian Languages: Volume 4: The Aboriginal Language of Melbourne and Other Grammatical Sketches. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1992.

"The Gurindji people are famous in Australia because they went on strike from Wave Hill Cattle Station in 1966, challenging the regime of dire poverty and exploitation which then existed on northern cattle stations where they worked as stockman, station hands and domestics. In the end, the strike turned out to be not just about wages and conditions but about land rights. After a change of government, the strike led to the return of some of the Gurindji traditional lands in 1975. This was a major factor which led to the enactment of Land Rights legislation for the Northern Territory in 1974 and 1976."

Wattie Creek or Dagaragu was chosen as the destination of the walk-off. Later, Kalkaringi was set up about 8 kms away on the Victoria River as a town to service the nearby stations. Many Gurindji moved to Kalkaringi and now both Kalkaringi and Dagaragu are home to the Gurindji. Kalkaringi contains most of the facilities such as the Community Office, school, abattoir, garage and shop. The CDEP office, a bakery and Batchelor Institute facilities can be found at Dagaragu. The walk-off is celebrated every year on 22 August as Freedom Day. The walk-off and subsequent return of traditional lands has been immortalised in music by the local band The Lazy Late Boys and by Paul Kelly's 'From Big Things, Little Things Grow' .

2. Language situation

Although the older people speak Gurindji, the main language spoken in these communities is Gurindji Kriol, which is being transmitted to the younger generations. Gurindji Kriol is used in a majority of contexts including family settings, the office and shop. Children are schooled at Kalkaringi in English. The school used to run a Gurindji language program (with the Gurindji speakers and a linguist from the Katherine Language Centre), however this has been discontinued.

3. Project

This part of the ACLA project was run at Dagaragu with eight families, who were very generous with their time and patience. Felicity Meakins visited the community every six months, and, together with Samantha Smiler Nangala, they recorded these families talking to their children. Felicity also interviewed people from different generations about their attitudes to Gurindji Kriol, and collected language texts to document Gurindji Kriol. The video and audio were transcribed and checked with Samantha Smiler on these field trips. The Dagaragu part of the project was supported by Diwurruwurru-jaru Aboriginal Corporation (Katherine Regional Aboriginal Language Centre) by the use of their vehicles, production facilities and office space. Dagaragu Council and Batchelor Institute allowed Felicity and Samantha to use the Batchelor caravan at Dagaragu. This project could not have been conducted without the support of these organisations.

Community Shop at Kalkaringi

4. References

- McConvell, P. "Changing places: European and Aboriginal styles," in Hercus, L., Hodges, F. and Simpson, J. (eds.,). The land is a map: Placenames of indigenous origin in Australia. Canberra, Pacific Linguistics and Pandanus Press, 2002, pp. 50-61

- Wavehill, Ronnie (Jangala) and Charola, Erika (trans.) Nyamuyinangkulu larrpa kujilirli yuwanani ngumpit-ma kartiya-rlu. Katherine: Diwurruwurru-jaru Aboriginal Corporation, 2002

- Dodson, Patrick. "Lingiari: Until the chains are broken," in Grattan, Michelle (ed.,). Reconciliation. Melbourne: Black Inc., 2000

- Hokari, Minoru. "From Wattie Creek to Wattie Creek: an oral historical approach to the Gurindji walk-off," in Aboriginal History 24, 2000, pp. 98-116

- Rangiari, Mick. "Talking history," in Yunupingu, Galarrwuy (ed.,). Our land is our life. Brisbane: UQ Press, 1997

- Long, Jeremy. "Frank Hardy and the 1966 Wave Hill walk-off," in Northern Perspective 19.2, 1996, pp. 1-9

- Rose, Deborah Bird. Hidden histories: black stories from Victoria River Downs, Humbert River and Wave Hill stations. Canberra: AIATSIS Press, 1991

- Doolan, J. "Walk-off (and later return) of various Aboriginal groups from cattle stations: Victoria River District, Northern Territory," in Berndt, R.M (ed.,). Aborigines and change: Australia in the '70s. Canberra: AIATSIS, 1977

- Hardy, Frank. The unlucky Australians. Melbourne: Nelson, 1968

Tennant Creek

1. History

"The post contact history of the Warumungu people is an unvarnished tale of the subordinaton of an Aboriginal soceity and its welfare to European interests... European settlement meant forced dispossession. This was not a once and for all process, but continued with the Warumungu being shunted around, right up to the 1960's, to accommodate various pastoral and mining interests." (Warumungu Land Claim Report No.31, 1988, p. 43)

Tennant Creek is the urban centre of Warumungu country. During the 1970's, the era of Federal government Self-Determination policy, Aboriginal people began to move or return to Tennant Creek from cattle stations and Warrabri Aboriginal settlement. In the face of opposition at their attempts to settle in the town, from authorities and European towns people, Aboriginal people began to establish organisations to gain representation, infrastructure and services for their community. Over the next decade a housing authority Warramunga Pabulu Housing Association (later Julali-kari Council), a health service Anyininginyi Congress and an office of the Central Land Council was opened. Today, Aboriginal people of the region have rights to country surrounding the town, claimed and recognised under the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976. The original Land Claim was lodged in 1978, for a decade the Warumungu fought for the return of their traditional lands. The ruling was made in 1988 and the hand back of the claim areas began soon after.

The individual histories of Aboriginal people in this region are rich and varied, and associated with places across Warumungu country. Some recollect living in camps at the old Telegraph Station. It had been established in 1872 as a repeater station for the Overland Telegraph line, the first European settlement in the region. It was built on the northern bank of the Tennant Creek, at Jurnkurakurr, a site of significance to the Warumungu.

At the Telegraph Station to the south at Barrow Creek, conflict between the local Kaytetye and Europeans broke out in the 1870's and lead to punitive expeditions, in which many Kaytetye, Warumungu, Anmatjerre, and Alyawarre and Warlpiri were killed. Conflict, largely over cattle, and resultant frontier violence occurred in many places in Central Australia in the first 50 years of settlement, causing the displacement of Aboriginal people. In the early 1900's Alyawarre and Wakaya fled violence at Hatcher's Creek and moved to Alexandria Station and other stations on the Barkly Tablelands. Many moved later to Lake Nash. Eastern Warlpiri people fled after the Coniston massacre in 1928, many onto Warumungu country.

By the 1890's it is estimated that 100 people were living at camps around the Tennant Creek Telegraph Station, some receiving rations, some worked for the station. Many came to the site during the 1891-93 droughts, to the perennial waterholes along the creek, which Warumungu people traditionally used in drought years. An area of dry country to the east of the Telegraph Station was gazetted as a Warumungu Reserve in 1892, to be revoked in 1934 to allow mining in the area.

In the 1930's gold was discovered, starting a gold rush, which brought hopefuls from across the country. Aboriginal people worked on the mines, many of which were located on what had been the Warumungu Reserve. Tennant Creek town was established in 1934, at a site 7 miles to the south of the Telegraph Station. It was off limits to Aboriginal people until the 1960's. Warumungu and Alyawarre people also worked at mines in the Davenport Murchinson Ranges, after wolfram discovered at Hatcher's Creek in 1913. Many Aboriginal people spent substantial periods of their lives there and on neighbouring Kurandi Station, where, in 1977 Aboriginal workers went on strike and staged a walk off.

The life histories of most people include their experiences living on cattle stations, which eventually surrounded the original site of European settlement. Vast tracts of Warumungu country had been granted as pastoral leases and were stocked from the 1880's onwards. Running cattle on these lands was incompatible with Aboriginal hunting and gathering practices and people were forced to settle on stations or the reserve. Many men worked as stockmen, drovers, butchers and gardeners, while women carried out domestic work in the station houses. Payment was generally in rations only and conditions were generally very poor.

W. E. Stanner, (later Professor Stanner) visited and reported to the Australian National Research Council in 1934 that

"The remnants of the Warumungu are scattered over a wide area between Banka Banka Station (on the Telegraph Line 95 km north of Tennant Creek) and Bonney Well, about 80 km south of Tennant Creek. East of the Telegraph Line they could be found at Rockhampton Downs and Alroy Downs. He estimated that all the remaining Warumungu numbered less than 100, 150 at most. These people lived within a circle of country about 200 to 240 km in diameter, with its centre between Tennant Creek and Alroy Downs. About 60 Aborigines were more or less permanently camped at the Tennant Creek, less than 20 of whom received rations from the Telegraph Station." (Warumungu Land Claim Report No. 31, 1988, p. 46)

Banka Banka, Bonney Well, Rockhampton Downs and Alroy Downs all cattle stations

Although people were dispersed and forced to settle on stations and at the reserve, they travelled extensively across Warumungu and neighbouring country, visiting family, taking up employment at different stations. Many older people recount today their travels in the 1930's-1960's. People walked, travelled in horse drawn buggies and later trucks and cars. During the Christmas holidays people moved to bush camps, where ceremonies continued to be conducted.

The last settlement to be established on Warumungu country, Mangka Manta or Phillip Creek Mission began in 1945. It was run by the Aboriginal Inland Mission until 1952, when the Native Affairs Branch took control. 215 people were moved there in 1945, most of them Warlpiri, from the west. The 1950's was the era of Assimilation and at Phillip Creek children were housed in dormitories, sent to the Mission School and instructed to adopt European ways. Part Aboriginal children were forcibly removed from their families here and sent to Darwin and Adelaide.

The Mission site was temporary for it lacked permanent water. An alternative site was found in 1954, over 100 km to the south of Tennant Creek, on Kaytetye and Alyawarre country. Phillip Creek was granted The new settlement was named Warrabri, a composite of 'Warrumungu' and 'Warlpiri', known today by its Kaytetye name Alekerenge. At Warrabri, there were people from a number of different language and country groups; Warumungu, Warlpiri, Kaytetye and Alyawarre. The move from Phillip Creek, which was compulsory, took place in 1956. Warrabri was intended to be a model Aboriginal settlement, where the new policy of Assimilation could be put into practice.

The Welfare Branch Report of 1961 states the policy of assimilation aimed at

"promoting and directing social change amongst the Australian aborigines in such a way that, whilst retaining connections with, and pride in, their ancestry they will become indistinguishable from other members of the Australian community in manner of life, standards of living, occupations and participation in community affairs." (Welfare Branch, Northern Territory Administration, Warrabri Aboriginal Reserve, September 1961, p. 6).

At Warrabri there was a strong focus on education and training. There was a school and adult education centre. By this time, there were also small schools on stations, often housed in caravans, known as silver bullets. Many young people were sent to secondary schools in Alice Springs and Darwin.

By the 1970's, nationwide Indigenous movements for rights to self determination and control of country were responded to with gradual political change from governments. The Assimilation policy was replaced by a policy of Self-Determination and Land Rights legislation was introduced. Warumungu and other Indigenous people returned to Tennant Creek to establish their community in changed political world. The history of the region is presented and celebrated in the Nyinkka Nyunyu Cultural Centre in Tennant Creek.

2. Demographics

The total population of Tennant Creek is approximately 6,300, 3,220 people are of Indigenous descent. Tennant Creek is a small, remote town, much like many other outback Australian towns. Its main street, a stretch of the Stuart Highway which links Adelaide and Darwin, is a parade of shops stretching about 3 kilometres through the town.

Tennant Creek is a remote service centre for the Barkly region, providing a wide range of amenities. There is a small hospital, numerous government agencies, an airport, town library, show grounds, a public pool and a variety of accommodation for tourists and employees of government and other service provision organisations, who visit the town. 500 km north of Alice Springs and 600 south of Katherine, the two closest population centres, Tennant Creek is a stop off point for travellers. The town's mining history is promoted to tourists and the old Battery is set up as a mining museum. In 2003 the Nyinkka Nyunyu Cultural Centre was opened, a purpose built centre, planned and designed in close consultation with local Indigenous people. The centre houses exhibitions on local history from an Indigenous point of view, cultural displays and local artwork.

There are a number of Indigenous organisations in the town, such as the local Aboriginal council and housing authority Julali-kari, the health centre Anyininginyi Congress, an office of the Central Land Council and the Barkly regional language centre, Papulu Apparr-kari. Most Indigenous people live in one of the 8 residential 'town camps', others live at 'street addresses', individual houses on residential streets in the town. The town camps are located on the edges of the town, generally large estates with up 20 houses situated at a distance from one another.

There is a primary and high school in the town, attended by both Indigenous and non-Indigenous children. In the 1970's and 80's, secondary students tended to leave Tennant Creek and board at secondary schools for Indigenous students in Darwin and Alice Springs, but nowadays young people tend to remain in Tennant Creek. An attempt was made in the 1990's to establish an independent Indigenous primary school, but this was unsuccessful.

3. Language situation

Tennant Creek is a multilingual community. Older people speak one or more traditional Indigenous languages. Individual multilingualism and multilingual identification may stem from a bi- or multilingual heritage, marriage, residential patterns or close social ties. People sometimes describe their language identity as 'going two ways, mother's side Warlmanpa, father's side Warumungu', for instance. The Preface to the 1988 Warumungu Land Claim Report no.31, by Aboriginal Land Commissioner, Justice Michael Maurice, attests the complexity of language use and affiliation in this region:

"the name by which the claim has come to be known [Warumungu Land Claim] is misleading for there are claimant groups whose principal language is either Wakaya, Alyawarre or Warlpiri, and others whose composition is difficult to define by reference to a principal language. Many are multilingual.[...]

Broadly speaking, the traditional language of Wakaya country is to the north east and east of Tennant Creek, Alyawarre is to the east and south east, Kaytetye is to the South, and Warlpiri to the west.

These living Aboriginal languages immediately give the claimants a cultural identity distinct from the rest of the world. The difference is not just tone deep; this inquiry illustrated that a different language necessarily entails different traditions, beliefs and values having a vitality all of their own. (Warumungu Land Claim Report No. 31, 1988, p. xi)

Today all of the languages mentioned above, with the exception of Wakaya and the addition of Warlmanpa, are spoken by older people in Tennant Creek. There are younger speakers of Warlpiri and Alyawarre, who have grown in or spent extensive periods in communities outside of Tennant Creek, where these languages continue to be vital and intergenerational transmission continues. Language shift from traditional Indigenous languages such as Warumungu and Warlmanpa to Aboriginal English (AE) and Creolised English (CE) varieties is advanced. Some children at Rockhampton Downs Station, a cattle station to the north of Tennant Creek, spoke Warumungu in the early 1980's, but intergeneration transmission of full proficiency ceased in most places before this time. Young and middle aged people have varying passive knowledge and may be partial speakers of a traditional language, allowing them to include traditional language phrases, lexemes and morphology in otherwise AE and CE discourse.

Aboriginal English and Creolised English are used in everyday communication between younger people and older people speaking with younger people. They are also the languages of socialisation of children. Many children hear and to some extent are addressed in traditional languages from older kin. Members of an extended families often share a house, live close by on the same town camp or visit regularly. For many children, an elderly relation acts as primary care giver all or some of the time. The language of education is Standard Australian English and people are also exposed to other standard varieties of English through popular music, TV, videos and DVD's.

There is no sustained history of language maintenance programs through the education system. Warumungu language classes ran in the primary school in the late 1980's and early 1990's and have intermittently and briefly since then. The Barkly regional language centre Papulu Apparr-kari currently runs an Indigenous language, culture and history program for High School students, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous. Papulu Apparr-kari also offers cultural awareness courses for non-Indigenous people working closely with Indigenous people and co-ordinates some language documentation projects.

4. References

- Edmunds, Mary. Frontiers: discourses of development in Tennant Creek. AIATSIS Press, 1995

- Maurice, M. Warumungu Land Claim. Report No.31. Report by the Aboriginal Land Commissioner, Mr Justice Maurice, to the Minister for Aboriginal Affairs and to the Administrator of the Northern Territory. Australian Government Publishing Service. Canberra, 1988

- Nash, David. "The Warumungu's Reserves 1892-1962: a case study in dispossession," in Australian Aboriginal Studies No.1, 1984

- Stanner, W. E. "Report to Australian National Research Council upon Aborigines and Aboriginal Reserve at Tennants Creek 1934," in AIAS Newsletter No.13, 1980

- Davison, Patricia. The Manga-Manda Settlement, Phillip Creek: an historical reconstruction from written, oral and material evidence. Material Culture Unit, James Cook University of North Queensland, 1979

- Welfare Branch, Northern Territory Administration. Unpublished report. Warrabri Aboriginal Reserve, 1961. IATSIS archive.

Yakanarra

1. Community

Yakanarra Community is situated on a small excision on Gogo Station, and lies approximately 80 kilometres south of Fitzroy Crossing in the Kimberley region of WA.

The Community was first established in 1989 and now has approximately 150 residents. Yakanarra has twenty-three (23) community houses, seven (7) staff houses, a store/office complex and a health centre which were constructed between 1993 and 2002. The independent school was established in July 1990 and currently caters for approximately 30 primary students and up to 20 junior secondary students, in five classes. The school also runs an itinerant students' class ('visiting school') for children visiting extended family in the community. In 2001, a small Adult Education Centre was established as an annexe of Karrayili Adult Education Centre, Fitzroy Crossing. Students here are predominantly completing the Certificate in General Education for Adults although there are some who are now completing diploma level studies with Notre Dame University, Broome.

2. Language situation

Yakanarra has a complex language ecology: the participants in the study have Walmajarri as their traditional language, Kimberley Kriol as their language of general use, and are exposed to standard English. People in Yakanarra are multi-lingual, and shift with varying degrees of facility between these three languages. Such language shift is largely determined by situational factors that include location, purpose, participants and language skills.

3. Project

The Aboriginal Child Language Acquisition (ACLA) project at Yakanarra commenced in 2003. Its central focus was a longitudinal study of some twelve children (aged between two and four) and the caregivers, relatives. friends and community members who make up their linguistic world. The project followed these children over three years and provided data for the overriding ACLA research questions about the nature of the children's language input, the effect of this on their language acquisition and their productive output, and the processes of language shift, maintenance and change which may be hypothesised to result from this multilingual environment. A particular focus of the Yakanarra research, however, was the role of questions in the interactions between the children and their interlocutors. Researchers in education and linguistics (Harris 1990, Eades 1993) have argued that the Aboriginal learning paradigm has little place for direct questions and in particular that the concept of 'false' or iterative questions, questions to which the enquirer already knows the answer, is unfamiliar to Aboriginal children. Much of this research is based on impressionistic language data; indeed, there is very little corpus-based or quantitative data on pre-school age indigenous children's language. The data collected at Yakanarra has been used to describe and analyse the nature of the questions asked of and by children and the responses that accompany such questions.

4. References

- Richards, Eilys; Hudson, Joyce and Lowe, Pat (eds.,). Out of the desert - stories of the Walmajarri. Broome: Magabala Books, 2002

- Lowe, Pat. Hunters and trackers of the Australian Desert. Rosenberg, 2002

- Peters, Sonja and Lofts, Pamela. (eds.,). Yarrtji - Six women's stories from the Great Sandy Desert. Aboriginal Studies Press, 1997

- Kimberley Language Resource Centre. Noola Bulla - in the shadow of the mountain. Broome: Magabala Books, 1996

- Pederen, Howard and Woorunmurra, Danjo. Jandamarra and the Bunuba resistance. Broome: Magabala Books, 1995

- Lowe, Pat and Pike, Jimmy. Jilji - life in the Great Sandy Desert. Broom: Magabala Books, 1990

- Marshall, Paul (ed.,). Raparapa - stories from the Fitzroy River drovers. Broome: Magabala Books, 1989